Sermon

Rabbi Anthony Lazarus Magrill, Mosaic Masorti Synagogue

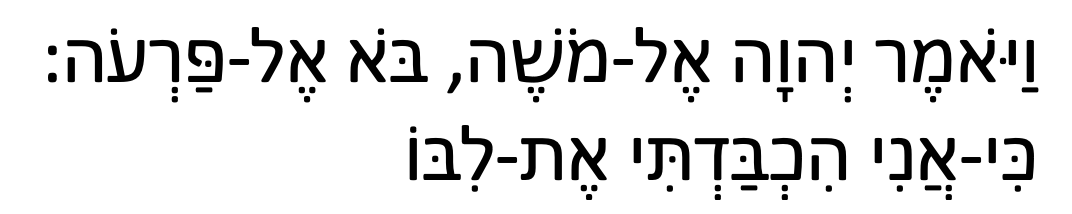

EXODUS 10:1

Come, then, to Pharaoh – for I have made his heart heavy.

This is the opening of Parshat Bo, and its Hebrew vocabulary is very revealing. God has been Hikhbad’ti Pharaoh’s heart – has ‘made it heavy’. This Hebrew root – Kuf-Beit-Ayin – is sometimes associated with heaviness; but more often with dignity, or even honour. The Torah will also repeatedly describe God as strengthening Pharaoh’s heart, as in: וְחִזַּקְתִּי אֶת-לֵב-פַּרְעֹה; v’Hizakti – ‘I will make it strong.’ (Ex 14.4)

There is a pattern here: words which are terms of praise in one context become indicators of pain or imbalance or disorder when applied to the heart. Just so, entering the Land of Israel, Moses enjoins us: Chazak v’Amatz! Be strong and of good courage! But isn’t the worst of Pharaoh’s heart that it should become chazak? And doesn’t the second Al Khet confession regret those sins we committed through imutz ha-Lev? This is another oft-repeated root; and another term which becomes an indicator of hardening, or of closing, when it is applied to the heart.

Three Hebrew roots – used to evoke strength, courage and honour – all now gesturing towards some kinds of illness, or pain, or temptation to wrongdoing. What might have become sweetness is deconstructed and reconfected, and gives rise only to bitterness; its ingredients having been distorted or set out of balance. This makes intuitive sense. We know that good attributes taken to excess have harmful-flipsides: honour finds its agonised opposite in pride; strength finds its strange twin in the refusal to own weakness; excess courage becomes an inability to ask for help. In all three, shame transforms a positive impulse into a source of discomfort and dis-ease.

Pharaoh is afflicted in ways which will be familiar to many of us who experience mental ill-health: he feels his heart is heavy, and closed off. He is unavailable to feelings of empathy or care. In his closed-off state, he hurts people: his community, his family and himself.

A wise strand of our tradition records just how many Jews chose not to leave Egypt, and how many of those who, even once they had left slavery, yearned soon afterwards to return to their confinement. Whatever it is that afflicts Pharaoh – his doubting, his isolation, his heavy-heartedness – it was clearly catching, and weighed down plenty of the Jewish people as well. The Meor Einayim, an 18th century Hasidic commentator on the Torah, describes the afflictions of Pharaoh’s heart alongside the Israelites’ peculiar spiritual dullness.

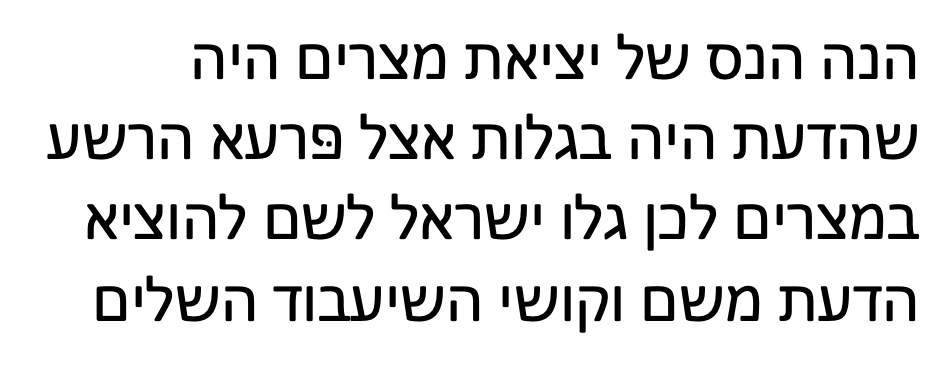

The great miracle of the Exodus was that Awareness (HaDa’at) was in exile with the wicked Pharaoh in Egypt. Therefore Israel, were exiled there too in order to bring it forth. The pain of their servitude made it whole.

Da’at – a broad term encompassing self-knowledge, intellect and sexuality – is described as having been exiled to Mitzrayim/Egypt. Indeed, the very name Mitzrayim indicates some kind of constriction or narrowness. The Meor Enayim, then, understands Egypt as a metaphor for some kind of rupture in the self; a disintegration affecting all those who dwell there, in the Narrow Place. Only the pain of enslavement brings eventual insight and healing.

Or, to put it another way, whilst we live in the Narrow Place, we are never truly ourselves – there is some facet of Da’at, some insight and awareness, which we lack and which we miss. Only upon leaving Egypt – drawing free from the Narrow Place – do Israel find freedom to make their own decisions, in full and integral insight. But one final claim is also made by the Meor Enayim: that before integration and wholeness become available, – a certain hardness, a certain suffering, has to be undergone first.

The fourth bracha of the weekday amidah blesses God who is חונן הדעת – Khonen haDa’at –who, in good grace, grants us Insight, or Awareness. This Awareness is a powerful force and there are many paths to it. I – it is perhaps the only force capable of transforming those qualities I mentioned above of imutz – courage, chizuk – strength, and kavod – honour, back from sources of shame into sources of light and fortitude. Insight – Da’at – is always striving for a God’s eye perspective on ourselves – striving for insight into the ways we help and harm ourselves, and into the ways even our best impulses misfire into ill-health.

Perhaps the Meor Enayim is right: one of the ways to come to insight may indeed be through an amount of inner suffering. Maybe there are things we learn about ourselves and our souls which only become clear once we’ve travelled a hard road to get them. That has certainly been my experience. And this is not to lionize mental suffering, but only to hope that its experience should not have been in vain for those who must be affected by it. For God, in our tradition, is also Khonen haDa’at. This is an understanding of the Divine which reaches out to us with the possibility of insight and improvement of self, that we in turn can reach towards autonomy and find new ways of doing better by and with ourselves. Parshat Bo, amongst other things, is a story about the difficulty we experience when we are closed to insight by our heaviness of heart. Bo also teaches that this hardness can come upon us without its being our, or anyone else’s, ‘fault’. But finally, Bo preaches the desirability of opening our heart; holds out the hope of learning about ourselves, and telling stories about ourselves (the therapeutic path to insight), which can thereby enable us to hold our disintegrating selves in balance. I hope you find yours.